Figure 1: Timeline for Medicare Drug Price Negotiation, Based on the First Year of Negotiated Price Availability (2025)

Juliette Cubanski, Tricia Neuman, and Meredith Freed

Published: Nov 23, 2021 - KFF

On November 19, 2021, the House of Representatives passed H.R. 5376, the Build Back Better Act (BBBA), which includes a broad package of health, social, and environmental proposals supported by President Biden. The BBBA includes several provisions that would lower prescription drug costs for people with Medicare and private insurance and reduce drug spending by the federal government and private payers. These proposals have taken shape amidst strong bipartisan, public support for the government to address high and rising drug prices. CBO estimates that the drug pricing provisions in the BBBA would reduce the federal deficit by $297 billion over 10 years (2022-2031).

The key prescription drug proposals included in the BBBA would:

This brief summarizes these provisions and discusses the expected effects on people, program spending, and drug prices and innovation. We incorporate the estimated budgetary effects released by CBO on November 18, 2021, and to provide additional context for understanding the expected budgetary effects, we point to past projections of similar legislative proposals from CBO and others. This summary is based on the legislative language included in the House-passed bill that may be modified as it moves through the Senate.

Under the Medicare Part D program, which covers retail prescription drugs, Medicare contracts with private plan sponsors to provide a prescription drug benefit. The law that established the Part D benefit includes a provision known as the “noninterference” clause, which stipulates that the HHS Secretary “may not interfere with the negotiations between drug manufacturers and pharmacies and PDP [prescription drug plan] sponsors, and may not require a particular formulary or institute a price structure for the reimbursement of covered part D drugs.” In addition, under current law, the Secretary of HHS does not negotiate prices for drugs covered under Medicare Part B (administered by physicians). Instead, Medicare reimburses providers based on a formula set at 106% of the Average Sales Price (ASP), which is the average price to all non-federal purchasers in the U.S, inclusive of rebates.

The Part D non-interference clause has been a longstanding target for some policymakers because it limits the ability of the federal government to leverage lower prices, particularly for high-priced drugs without competitors. And with the rise in the number of high-priced drugs coming to market, including the recently-approved Alzheimer’s drug priced at $56,000, which would be covered under Part B, there is renewed interest in proposals to allow the federal government to negotiate drug prices for Medicare beneficiaries. A recent KFF Tracking Poll finds large majorities support allowing the federal government to negotiate and this support holds steady even after the public is provided the arguments being presented by parties on both sides of the legislative debate.

The BBBA would amend the non-interference clause by adding an exception that would allow the federal government to negotiate prices with drug companies for a small number of high-cost drugs covered under Medicare Part D (starting in 2025) and Part B (starting in 2027). The negotiation process would apply to no more than 10 (in 2025), 15 (in 2026 and 2027), and 20 (in 2028 and later years) single-source brand-name drugs or biologics that lack generic or biosimilar competitors. These drugs would be selected from among the 50 drugs with the highest total Medicare Part D spending and the 50 drugs with the highest total Medicare Part B spending. The negotiation process would also apply to all insulin products.

The legislation exempts from negotiation drugs that are less than 9 years (for small-molecule drugs) or 13 years (for biological products, based on the Manager’s Amendment) from their FDA-approval or licensure date. The legislation also exempts “small biotech drugs” from negotiation until 2028, defined as those which account for 1% or less of Part D or Part B spending and account for 80% or more of spending under each part on that manufacturer’s drugs, as well as drugs with Medicare spending of less than $200 million in 2021 (increased by the CPI-U for subsequent years) and drugs with an orphan designation as their only FDA-approved indication.

The proposal establishes an upper limit for the negotiated price (the “maximum fair price”) equal to a percentage of the non-federal average manufacturer price: 75% for small-molecule drugs more than 9 years but less than 12 years beyond approval; 65% for drugs between 12 and 16 years beyond approval or licensure; and 40% for drugs more than 16 years beyond approval or licensure. Part D drugs with prices negotiated under this proposal, including insulin, would be required to be covered by all Part D plans. Medicare’s payment to providers for Part B drugs with prices negotiated under this proposal would be 106% of the maximum fair price (rather than 106% of the average sales price under current law). (In a separate provision of the BBBA, section 13940, Medicare payments to providers for the administration of biosimilar biologic products would be increased to 108% between April 1, 2022 through March 31, 2027.)

An excise tax would be levied on drug companies that do not comply with the negotiation process. Manufacturers would face an escalating excise tax on total sales of the drug in question, starting at 65% and increasing by 10% every quarter to a maximum of 95%. In addition, manufacturers that refuse to offer an agreed-upon negotiated price for a selected drug to “a maximum fair price eligible individual” (i.e., Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in Part B and/or Part D, depending on the selected drug) or to a provider of services to maximum fair price eligible individuals (such as a physician or hospital) would pay a civil monetary penalty equal to 10 times the difference between the price charged and the maximum fair price.

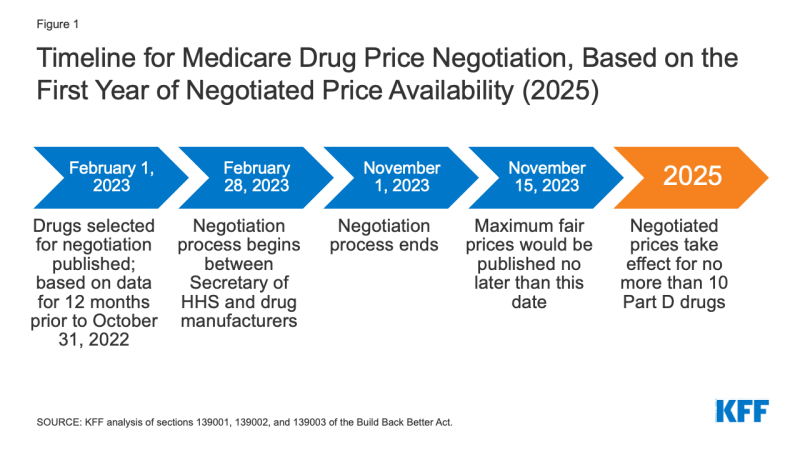

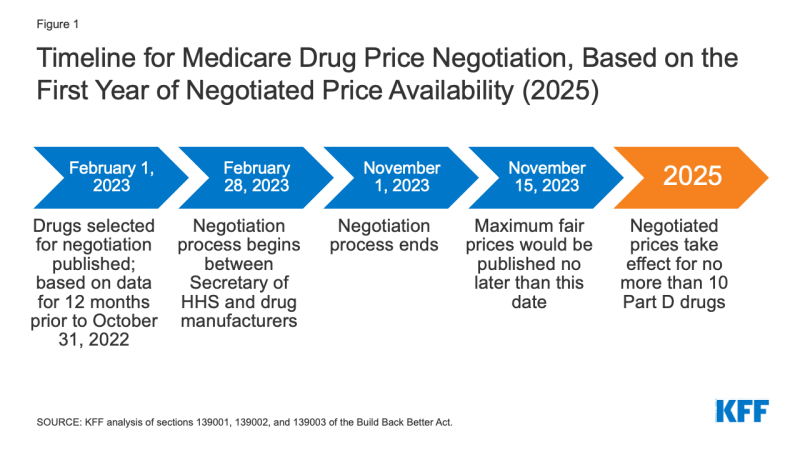

The timeline for the negotiation process spans a roughly two-year period (Figure 1). To make negotiated prices available in 2025, the list of selected drugs for negotiation would be published on February 1, 2023, based on data for a 12-month period prior to October 31, 2022. The period of negotiation between the Secretary and manufacturers of Part D drugs would occur between February 28, 2023 and November 1, 2023, and the negotiated “maximum fair prices” would be published on the website CMS.gov no later than November 15, 2023. The initial period of negotiation for Part B drugs would take place between February 28, 2025 and November 1, 2025, for prices established for 2027.

Figure 1: Timeline for Medicare Drug Price Negotiation, Based on the First Year of Negotiated Price Availability (2025)

The legislation appropriates 10-year (2022-2031) funding of $3 billion for implementing the drug price negotiation provisions.

Effective Date: The negotiated prices for the first set of selected drugs (covered under Part D) would take effect in 2025. For drugs covered under Part B, negotiated prices would take effect in 2027.

The provision to allow the Secretary to negotiate drug prices would put downward pressure on both Part D premiums and out-of-pocket drug costs, although the number of Medicare beneficiaries who would see lower out-of-pocket drug costs in any given year under this provision, and the magnitude of savings, would depend on how many and which drugs were subject to the negotiation process and the price reductions achieved through the negotiations process relative to current prices.

Neither CBO nor the Administration have published estimates of beneficiary premium and out-of-pocket budget effects associated with the BBBA proposal to allow the HHS Secretary to negotiate drug prices. An earlier version of the negotiations proposal in H.R.3 that passed the House of Representatives in 2019 would have lowered cost sharing for Part D enrollees by $102.6 billion in the aggregate (2020-2029) and Part D premiums for Medicare beneficiaries by $14.3 billion, according to estimates from the CMS Office of the Actuary (OACT). Based on our analysis of the H.R. 3 version of this provision, the negotiations provision in H.R. 3 would have reduced Medicare Part D premiums for Medicare beneficiaries by an estimated 9% of the Part D base beneficiary premium in 2023 and by as much as 15% in 2029. However, the effects on beneficiary premiums and cost sharing under the drug negotiation provision in the BBBA are expected to be more modest than the effects of H.R. 3 due to the smaller number of drugs eligible for negotiation and a different method of calculating the maximum fair price.

CBO estimates $78.8 billion in Medicare savings over 10 years (2022-2031) from the drug negotiation provisions in the BBBA.

Based on earlier legislation (H.R. 3) that would have allowed the Secretary to negotiate prices for a larger number of drugs and apply negotiated rates to private insurance, CBO estimated over $450 billion in 10-year (2020-2029) savings from the Medicare drug price negotiation provision, including $448 billion in savings to Medicare and $12 billion in savings for subsidized plans in the ACA Marketplace and the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program. CBO also estimated an increase in revenues of about $45 billion over 10 years resulting from lower drug prices available to employers, which would reduce premiums for employer-sponsored insurance, leading to higher compensation in the form of taxable wages.

A separate CBO estimate of the same Medicare drug price negotiation provision included in another House bill in the 116th Congress (H.R. 1425, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Enhancement Act) estimated higher 10-year (2021-2030) savings of nearly $530 billion, mainly because it would allow the Secretary to negotiate prices for a somewhat larger set of drugs in year 2 of the negotiation program.

CBO estimates that the drug pricing provisions in the Build Back Better Act will have a very modest impact on the number of new drugs coming to market in the U.S. over the next 30 years: 10 fewer out of 1,300, or a reduction of 0.8% (about 1 over the 2022-2031 period, about 4 over the subsequent decade, and about 5 over the decade after that). The expected impact on drug development is more limited than suggested by a prior estimate from CBO in part because the drug price negotiation proposal in the BBBA would affect prices for fewer drugs, and with a different upper limit, than H.R. 3. CBO had estimated that a drug price negotiation proposal along the lines of that which was included in H.R. 3 would lead to 2 fewer drugs in the first decade (a reduction of 0.5%), 23 fewer drugs over the next decade (a reduction of 5%), and 34 fewer drugs in the third decade (a reduction of 8%).

Under current law, Medicare has no authority to limit annual price increases for drugs covered under Part B (which includes those administered by physicians) or Part D. In contrast, Medicaid has a rebate system that requires drug manufacturers to provide refunds if prices grow faster than inflation. Year-to-year drug price increases exceeding inflation are not uncommon and affect people with both Medicare and private insurance. Our analysis shows that half of all covered Part D drugs had list price increases that exceeded the rate of inflation between 2018 and 2019. A separate analysis by the HHS Office of Inspector General showed average sales price (ASP) increases exceeding inflation for 50 of 64 studied Part B drugs in 2015.

The BBBA would require drug manufacturers to pay a rebate to the federal government if their prices for single-source drugs and biologicals covered under Medicare Part B and nearly all covered drugs under Part D increase faster than the rate of inflation (CPI-U). Under these provisions, price changes would be measured based on the average sales price (for Part B drugs) or the average manufacturer price (for Part D drugs). If price increases are higher than inflation, manufacturers would be required to pay the difference in the form of a rebate to Medicare.

The rebate amount is equal to the total number of units multiplied by the amount if any by which the manufacturer price exceeds the inflation-adjusted payment amount, including all units sold outside of Medicaid and therefore applying to use by Medicare beneficiaries, privately insured, and uninsured individuals. This means drug manufacturers would effectively have to rebate to the government any revenues from price increases in excess of inflation in Medicare or private insurance plans. Rebate dollars would be deposited in the Medicare Supplementary Medical Insurance (SMI) trust fund.

Manufacturers that do not pay the requisite rebate amount would be required to pay a penalty equal to at least 125% of the original rebate amount. The base year for measuring cumulative price changes relative to inflation is 2021.

The legislation appropriates 10-year (2022-2031) funding of $160 million to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) for implementing the inflation rebate provisions ($80 million for Part B and $80 million for Part D).

Effective Date: These provisions would take effect in 2023.

This proposal is expected to limit out-of-pocket drug spending growth for people with Medicare and private insurance and put downward pressure on premiums by discouraging drug companies from increasing prices faster than inflation. The number of Medicare beneficiaries and privately insured individuals who would see lower out-of-pocket drug costs in any given year under this provision would depend on how many and which drugs had lower price increases and the magnitude of price reductions relative to current prices under each provision. Based on our analysis, prices have increased faster than inflation for many Part D covered drugs, suggesting that inflation rebates would produce savings for a large number of Medicare beneficiaries.

CBO estimates a net federal deficit reduction of $83.6 billion over 10 years (2022-2031) from the drug inflation rebate provisions in the BBBA. This includes net savings of $49.4 billion ($61.8 billion in savings to Medicare and $7.7 billion in savings for other federal programs, such as DoD, FEHB, and subsides for ACA Marketplace coverage, offset by $20.1 billion in additional Medicaid spending) and higher federal revenues of $34.2 billion.

Previously, CBO estimated savings from the drug inflation rebate provisions in legislation under consideration in 2019 (H.R. 3 and S. 2543, Senate Finance Committee legislation considered in the 116th Congress) amounting to $36 billion for H.R. 3 (2020-2029) and $82 billion for S. 2543 (2021-2030); 10-year savings were estimated to be lower under H.R. 3 because the inflation provision would not apply to drugs subject to the government negotiation process that would be established by that bill. This same exception applies in the BBBA, but fewer drugs could be exempted because fewer drugs are subject to negotiations in the BBBA than H.R.3.

Drug manufacturers may respond to the inflation rebates by increasing launch prices, which could result in some Medicare beneficiaries and Medicare itself paying higher prices for new drugs, and potentially lead to higher costs for other payers and privately insured patients. While Part D and commercial insurance plans can negotiate with drug companies and refuse to cover drugs with very high launch prices, they may have less leverage in some instances, such as when there are no therapeutic alternatives available or when drugs are covered under a “protected class”. If launch prices rise for Part B drugs, the HHS Secretary would have no authority to negotiate lower prices unless and until the new drug meets the criteria for selection for drug price negotiation under the separate BBBA provision described above.

Medicare Part D currently provides catastrophic coverage for high out-of-pocket drug costs, but there is no limit on the total amount that beneficiaries pay out of pocket each year. Medicare Part D enrollees with drug costs high enough to exceed the catastrophic coverage threshold are required to pay 5% of their total drug costs above the threshold unless they qualify for Part D Low-Income Subsidies (LIS). Medicare pays 80% of total costs above the catastrophic threshold (known as “reinsurance”) and plans pay 15%. Medicare’s reinsurance payments to Part D plans now account for close to half of total Part D spending (45%), up from 14% in 2006 (increasing from $6 billion in 2006 to $48 billion in 2020).

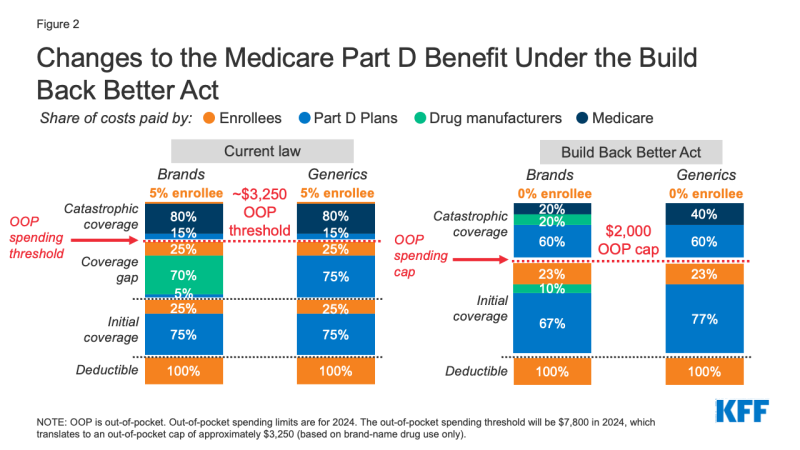

Under the current structure of Part D, there are multiple phases, including a deductible, an initial coverage phase, a coverage gap phase, and the catastrophic phase. When enrollees reach the coverage gap benefit phase, they pay 25% of drug costs for both brand-name and generic drugs; plan sponsors pay 5% for brands and 75% for generics; and drug manufacturers provide a 70% price discount on brands (there is no discount on generics). Under the current benefit design, beneficiaries can face different cost-sharing amounts for the same medication depending on which phase of the benefit they are in, and can face significant out-of-pocket costs for high-priced drugs because of coinsurance requirements and no hard out-of-pocket cap.

The BBBA amends the design of the Part D benefit by adding a hard cap on out-of-pocket spending set at $2,000 in 2024, increasing each year based on the rate of increase in per capita Part D costs (Figure 2). It also lowers beneficiaries’ share of total drug costs below the spending cap from 25% to 23%. The provision lowers Medicare’s share of total costs above the spending cap (“reinsurance”) from 80% to 20% for brand-name drugs and to 40% for generic drugs; increases plans’ share of costs from 15% to 60% for both brands and generics; and adds a 20% manufacturer price discount on brand-name drugs. The BBBA also requires manufacturers to provide a 10% discount on brand-name drugs in the initial coverage phase (below the annual out-of-pocket spending cap), instead of a 70% price discount in the coverage gap phase under the current benefit design.

Figure 2: Changes to the Medicare Part D Benefit Under the Build Back Better Act

The legislation increases the Medicare premium subsidy for the cost of standard drug coverage to 76.5% (from 74.5% under current law) and reduces the beneficiary share of the cost to 23.5% (from 25.5%). The legislation also allows beneficiaries the option of smoothing out their out-of-pocket costs over the year rather than face high out-of-pocket costs in any given month.

Effective Date: The Part D benefit redesign, including the $2,000 out-of-pocket cap and the premium subsidy changes would take effect in 2024. The provision to smooth out-of-pocket costs would take effect in 2025.

Medicare beneficiaries in Part D plans with relatively high out-of-pocket drug costs are likely to see substantial out-of-pocket cost savings from this provision. This would include Medicare beneficiaries with spending above the catastrophic threshold due to just one very high-priced specialty drug for medical conditions such as cancer, hepatitis C, or multiple sclerosis and beneficiaries who take a handful of relatively costly brand or specialty medications to manage their medical condition.

While most Part D enrollees have not had out-of-pocket costs high enough to exceed the catastrophic coverage threshold in a single year, the likelihood of a Medicare beneficiary incurring drug costs above the catastrophic threshold increases over a longer time span. Our analysis shows that in 2019, nearly 1.5 million Medicare Part D enrollees had out-of-pocket spending above the catastrophic coverage threshold. Looking over a five-year period (2015-2019), the number of Part D enrollees with out-of-pocket spending above the catastrophic threshold in at least one year increases to 2.7 million, and over a 10-year period (2010-2019), the number of enrollees increases to 3.6 million.

Based on our analysis, 1.2 million Part D enrollees in 2019 incurred annual out-of-pocket costs for their medications above $2,000 in 2019, averaging $3,216 per person. Based on their average out-of-pocket spending, these enrollees would have saved $1,216, or 38% of their annual costs, on average, if a $2,000 cap had been in place in 2019. Part D enrollees with higher-than-average out-of-pocket costs could save substantial amounts with a $2,000 out-of-pocket spending cap. For example, the top 10% of beneficiaries (122,000 enrollees) with average out-of-pocket costs for their medications above $2,000 in 2019 ・who spent at least $5,348 ・would have saved $3,348 (63%) in out-of-pocket costs with a $2,000 cap.

While a $2,000 out-of-pocket spending cap and the reduction in beneficiary coinsurance from 25% to 23% below the cap are expected to lower out-of-pocket drug spending by Part D enrollees, it is also possible that enrollees could face higher Part D premiums resulting from higher plan liability for drug costs above the spending cap. To mitigate the potential premium increase, the BBBA increased the federal portion of the Medicare premium subsidy from 74.5% to 76.5% and reduced the beneficiary share of cost from 25.5% to 23.5%. Plans could also adopt strategies to exercise greater control of costs below the cap, such as through more utilization management or a stronger push for generic utilization, which could also limit potential premium increases.CBO estimates the benefit redesign and smoothing provisions of the BBBA would reduce federal spending by $1.5 billion over 10 years (2022-2031), which consists of $1.6 billion in lower spending associated with Part D benefit redesign and $0.1 billion in higher spending associated with the provision to smooth out-of-pocket costs.

For Medicare beneficiaries with diabetes who use insulin, coverage is provided under Medicare Part D, the outpatient prescription drug benefit. Because Part D plans vary in terms of the insulin products they cover and costs per prescription, what enrollees pay for insulin products also varies. Insulin coverage and costs also vary for people with private coverage.

Medicare beneficiaries can choose to enroll in a Part D plan participating in an Innovation Center model in which enhanced drug plans cover insulin products at a monthly copayment of $35 in the deductible, initial coverage, and coverage gap phases of the Part D benefit. Participating plans do not have to cover all insulin products at the $35 monthly copayment amount, just one of each dosage form (vial, pen) and insulin type (rapid-acting, short-acting, intermediate-acting, and long-acting). In 2022, a total of 2,159 Part D plans will participate in this model, a 32% increase in participating plans since 2021. Based on August 2021 enrollment, 45% of non-LIS enrollees are in PDPs that will participate in the insulin model in 2022. This model is not available to people outside of Medicare, however. The model was launched in response to rising prices for insulin, which have attracted increasing scrutiny from policymakers, leading to congressional investigations and overall concerns about affordability and access for people with diabetes who need insulin to control blood glucose levels.

The BBBA would require insurers, including Medicare Part D plans and private group or individual health plans, to charge patient cost-sharing of no more than $35 per month for insulin products. Private group or individual plans would not be required to cover all insulin products, just one of each dosage form (vial, pen) and insulin type (rapid-acting, short-acting, intermediate-acting, and long-acting), for no more than $35.

Medicare Part D plans, both stand-alone drug plans and Medicare Advantage drug plans, would be required to charge no more than $35 for whichever insulin products they cover in 2023 and 2024 and all insulin products beginning in 2025. Coverage of all insulin products would be required beginning in 2025 because the drug negotiation provision described earlier would require all Part D plans to cover all negotiation-eligible drugs, and all insulin products are subject to negotiation under that provision.

Effective Date: These provisions would take effect in 2023.

A $35 cap on monthly cost sharing for insulin products is expected to lower out-of-pocket costs for insulin users with private insurance and those in Medicare Part D without low-income subsidies. In 2017, 3.1 million Medicare Part D enrollees used insulin. Among insulin users without Part D low-income subsidies (LIS), average annual per capita out-of-pocket spending on insulin increased by 79% over these years, from $324 in 2007 to $580 in 2017. Average annual growth in costs was 6%, which exceeded the 1.6% average annual rate of growth in inflation over this period. If Part D enrollees had paid 12 months of $35 copays for insulin in 2017, annual costs for one insulin product would have been $420, or $160 (28%) lower than average annual costs paid by non-LIS Part D insulin users in 2017.

According to our analysis of 2019 Part D formularies, a large number of Part D plans placed insulin products on Tier 3, the preferred drug tier, which typically had a $47 copayment per prescription during the initial coverage phase. However, once enrollees reached the coverage gap phase, they faced a 25% coinsurance rate, which equates to $100 or more per prescription in out-of-pocket costs for many insulin therapies, unless they qualified for low-income subsidies. Paying a flat $35 copayment rather than 25% coinsurance or a higher copayment amount could reduce out-of-pocket costs for many insulin products. These provisions are also expected to provide savings to millions of insulin users with private coverage.

CBO estimates additional federal spending of $1.4 billion ($0.9 billion for Medicare and $0.5 billion in other federal spending) and a reduction in federal revenues of $4.6 billion over 10 years associated with the insulin cost-sharing limits in the BBBA.

Medicare covers vaccines under both Part B and Part D. This separation of coverage for vaccines under Medicare is because there were statutory requirements for coverage of a small number of vaccines under Part B before the 2006 start of the Part D benefit. Vaccines for COVID-19, influenza, pneumococcal disease, and hepatitis B (for patients at high or intermediate risk), and vaccines needed to treat an injury or exposure to disease are covered under Part B. All other commercially available vaccines needed to prevent illness are covered under Medicare Part D.

For the influenza, pneumococcal pneumonia, hepatitis B, and COVID-19 vaccines covered under Medicare Part B, patients currently face no cost sharing for either the vaccine itself or its administration. For other Part B vaccines, such as those needed to treat an injury or exposure to a disease such as rabies or tetanus, Medicare covers 80% of the cost, and beneficiaries are responsible for the remaining 20%. Unlike most vaccines covered under Part B, vaccines covered under Part D can be subject to cost sharing, because Part D plans have flexibility to determine how much enrollees will be required to pay for any given on-formulary drug, including vaccines. (Part D enrollees who receive low-income subsidies (LIS) generally pay relatively low amounts for vaccines and other covered drugs.) Under Part D, cost sharing can take the form of flat dollar copayments or coinsurance (i.e., a percentage of list price).

The BBBA would require that adult vaccines covered under Medicare Part D that are recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), such as for shingles, be covered at no cost. This would be consistent with coverage of vaccines under Medicare Part B, such as the flu and COVID-19 vaccines.

Effective Date: This provision would take effect in 2024.

Eliminating cost-sharing for adult vaccines covered under Medicare Part D could help with vaccine uptake among older adults and would lower out-of-pocket costs for those who need Part D-covered vaccines. Our analysis shows that in 2018, Part D enrollees without low-income subsidies paid an average of $57 out of pocket for each dose of the shingles shot, which is generally free to most other people with private coverage.

CBO estimates that this provision would increase federal spending by $3.3 billion over 10 years (2022-2031).

The BBBA would prohibit implementation of the November 2020 final rule issued by the Trump Administration that would have eliminated rebates negotiated between drug manufacturers and pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) or health plan sponsors in Medicare Part D by removing the safe harbor protection currently extended to these rebate arrangements under the federal anti-kickback statute. This rule was slated to take effect on January 1, 2022, but the Biden Administration delayed implementation to 2023 and the infrastructure legislation signed into law on November 15, 2021 includes a further delay to 2026.

Effective Date: This provision would take effect in 2026.

Since the rebate rule never took effect, repealing it is not expected to have a material impact on Medicare beneficiaries. Had the rule taken effect, it was expected to increase premiums for Medicare Part D enrollees, according to both CBO and the HHS Office of the Actuary (OACT). OACT estimated that a small group of beneficiaries who use drugs with significant manufacturer rebates could have seen a substantial decline in their overall out-of-pocket spending under the rule, assuming manufacturers passed on price discounts at the point of sale, but other beneficiaries would have faced out-of-pocket cost increases.

Because the rebate rule was finalized (although not implemented), its cost has been incorporated in CBO’s baseline for federal spending. Therefore, repealing the rebate rule is expected to generate savings. CBO estimates savings of $142.6 billion from the repeal of the Trump Administration’s rebate rule between 2026 (when the BBBA provision takes effect) and 2031. In addition, CBO estimated savings of $50.8 billion between 2023 and 2026 for the three-year delay of this rule included in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. This is because both CBO and Medicare’s actuaries estimated substantially higher Medicare spending over 10 years as a result of banning drug rebates under the Trump Administration’s rule ・up to $170 billion higher, according to CBO, and up to $196 billion higher, according to the HHS Office of the Actuary (OACT).